… walk into a bar. I wish I could turn that into a joke, but it happens to be deadly serious. Anyone even remotely following the life of the Church must be acutely aware of the multitude of dissenting groups both in and outside it. The spectrum ranges from the Austrian priests via the US nuns all the way to the Society of St. Pius X (who were largely responsible for the attacks on Archbishop Müller’s words on the Eucharist and Mary’s virginity that I discussed before). While it would be interesting to engage in their arguments, here I would instead like to look at the bigger picture: conscience.

What the Church teaches about conscience is, to my mind, key not only to seeking God’s will but applicable to all - believers and non-believers alike - as a basis for an honest and conscious life. Let's start with how the Catechism introduces the topic (and forgive me for keeping this brief - it is a section that I am very fond of and would love to expand on in the future):

“Deep within his conscience man discovers a law which he has not laid upon himself but which he must obey. Its voice, ever calling him to love and to do what is good and to avoid evil, sounds in his heart at the right moment.... For man has in his heart a law inscribed by God.... His conscience is man’s most secret core and his sanctuary. There he is alone with God whose voice echoes in his depths.” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, §1776)I read this as saying that we have in us a sense of right and wrong that is not self–imposed and that Christians believe to come from God. While agnostics/atheists would hold other views on its origin, the key here is that I don’t choose what I myself consider right or wrong.

Next, the Catechism exhorts us to self–examination and reflection - very much in the tradition of philosophers ever since Socrates:

It is important for every person to be sufficiently present to himself in order to hear and follow the voice of his conscience. This requirement of interiority is all the more necessary as life often distracts us from any reflection, self-examination or introspection (CCC, §1779)Finally, after providing numerous ways to inform one’s conscience, listing a couple of rules (never do evil so that good may result from it, the golden rule, respecting one’s neighbor) and elaborating on the fact that one’s conscience can be erroneous, the Catechism categorically states:

A human being must always obey the certain judgment of his conscience. If he were deliberately to act against it, he would condemn himself. (CCC, §1790)In other words, if, after having scrutinized and examined your own conscience you get to a conclusion you are certain of, the Church teaches you to follow it no matter what. The conclusion you arrive at may be erroneous in the Church’s eyes and you may be admonished, gagged and even punished for your views, but under no circumstances are you to act against what your conscience, with the help of your reason (CCC, §1786), arrives at as being certain.

Seen from the perspective of an individual this is quite tricky, when their conscience leads them into conflict with the Church’s teaching. Imagine you arrive at a judgment that you are certain of but that is contrary to what the Church says. Are you to disregard your own conscience and fall into line, or are you to dissent? The Catechism warns against the former, but you may incur penalties for the latter, which would give you every right to say: ‘Hey, but you told me to follow my conscience! What gives?!’ This is how many who today are voicing their opinions must feel and I can see how that would be very frustrating.

If we look at this picture from the perspective of the whole Church and over its history, another aspect emerges though, which is that dissent, which may at first be punished, can end up being rewarded later. Often the changes that take place in the Church’s teachings are prefigured in its saints, who - being faithful to their consciences and committed to listening to God's voice - often have to pay a heavy price for sticking their necks out when most others in the Church have not yet caught on to a new impulse from the Holy Spirit. In fact, suspicion on the part of Church authorities is a pretty constant feature of the lives of the saints (e.g., St. Ignatius of Loyola being questioned by the Inquisition three times, St. John of the Cross being imprisoned by his fellow Carmelites and many others), which brings me to the most severe form of punishment at the Church’s disposal: excommunication.

Excommunication is the severest penalty the Church can impose and results in the excommunicated member being deprived from participating in the life of the Church. It ought to be used as a ‘medicinal’ penalty, meant to correct rather than punish or make satisfaction for the wrong done. Those who have over the centuries proclaimed heresies or lead to schisms in the Church have been excommunicated, but the list also includes a number of saints - in other words, people whom the Church holds up as examples of how to follow the teachings of Jesus and his Church. These saints, who at some point of their lives were excommunicated (and whose excommunications were later either declared invalid or lifted) include St. Joan of Arc (for insubordination to a bishop - declared invalid), St. Mary MacKillop (for reporting a paedofile priest and insisting he be removed - declared invalid), St. Hippolytus (the first antipope, excommunicated, but later reconciled with the pope’s successor who lifted the excommunication - incidentally all three: the two popes and Hippolytus are saints), whose feast day is tomorrow, and finally St. Athanasius, now revered as the ‘Father of Orthodoxy’ (excommunicated by a pope influenced by the Arian heresy but exonerated by his successor).

Maybe the picture emerging here is one of it being just fine to ignore Church teaching and to just go with whatever comes into one’s head. This is not where I am going at all. There is a clear tension between faithfulness to Church teaching and fidelity to one’s own conscience, where - for an individual – the latter wins in the end. However, let us not side-step the elephant in the room: certainty! If you look back at the Catechism’s teaching, it says that ‘a human being must always obey the certain judgment of his conscience’ [emphasis mine] - not just a hunch or even an conclusion that is gathering support or one that has good statistical chances, but certainty! And, in the process of reflecting and analyzing one’s judgment, Catholics are called to take Church teaching and a host of other factors into account. Only after having undergone a rigorous and well informed process and only if this process has lead them to interior certainty are they commanded to follow their own conscience over Church teaching. This is pretty strong stuff and certainly sorts out the wheat from the chaff. In fact, if you look at the vast majority of saints who have come under suspicion in the Church’s eyes, the way they responded to them - with humility, but with determination – was in many cases a contributor to those suspicions having been dissolved.

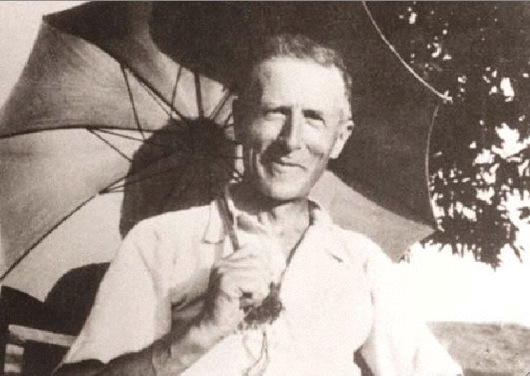

To conclude, let me just point to an example that to me shines most brightly - that of Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, the French Jesuit, philosopher, paleontologist and geologist, who was one of the most radical and creative thinkers of recent centuries. His ideas (on which more at a later date) are to this day viewed with suspicion by the Church and carry a warning about being ‘offensive to Catholic doctrine’ (although Pope Benedict XVI recently referred to them favorably). The most impressive thing to me about Teilhard de Chardin though is his humility and obedience. When asked by the Church to cease his writings and teachings, he and the Jesuit order complied. This, to my mind was a tremendously selfless act and one that also demonstrated Teilhard de Chardin’s priorities: obedience and poverty before fame and glory. I believe his insights will one day be exonerated and become part of Catholic patrimony.

No comments:

Post a Comment