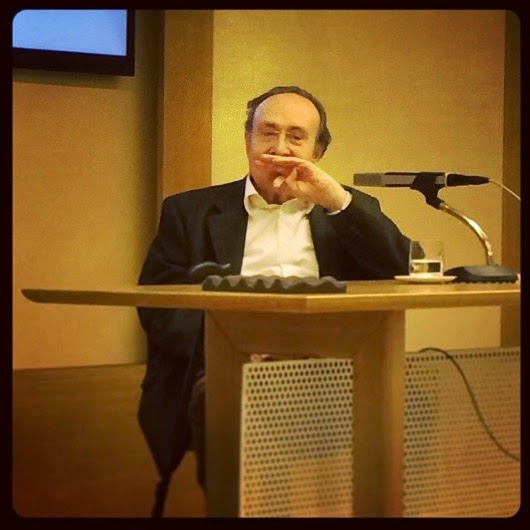

Today, at the age of 85, the man who has helped me most with understanding God has gone to be with Him. Giuseppe Maria Zanghí, known simply as Peppuccio to all who met him (the Italian diminutive for Joseph that in English would be rendered as Joey), was a follower and close collaborator of Chiara Lubich, whose process of beatification is completing its diocesan phase and transferring to the Vatican on Tuesday.

Peppuccio’s philosophical genius will, I am certain, provide the basis for a deeper understanding of God for many generations to come. His insights into the fundamental interconnectedness of being and not being as the key to love and to an intuition of the value of suffering are akin to Einstein’s theory of relativity in that they turn all that came before on its head, while, at the same time, being a superset of it. Having had the privilege to listen to him speak and to get to know him personally a little has been a great gift for me and I will never forget meeting him again last May, after not seeing him for many years. By that time he had become a frail, old man, whose former steel had given way to the warmth of a kindly grandfather. I will never forget his recognizing me and caressing my face like my own grandfather used to.

Dearest Peppuccio, I will miss you very much! Thank you for all you have taught me!

Instead of telling you more about his extraordinary life, I prefer to translate for you an excerpt from a paper he wrote in 1979, entitled “Identity and dialogue,” so that you may get a flavor of his extraordinary thought directly.

In this paper Peppuccio considers the challenges and seeming opposition of the concepts of individual identity on the one hand and of dialogue on the other. Let’s join Peppuccio’s train of thought at the point where he presents how God loves us without possessing us, after having presented profound analyses of both identity and dialogue in isolation:

“I can be myself in Him (being an intimate participant of Trinitarian life in the Word), while being really distinct from Him (by virtue of being a creature different from Him). It is His love that wants me, and the love of God does not withdraw into itself, canceling diversity with the other by totally reverting it to Himself, but “makes” the other and guards them in diversity from Himself, not wanting to possess (like He doesn’t possess Himself) in total reabsorption.Peppuccio here roots our diversity-preserving union with God and our own relationships with others in His own inner life, where God’s relationship of love to all is the basis of our own diversity-preserving union with them. He then spells out the consequences of a departure from this many-but-one life:

And also those who are other than me, the other, or other subjects, are really different from me, because they are “guarded” in the diversity of God, and yet we are one because we are all seized by the same movement of God’s love.”

“If I remove myself from the ecstasy of love, the ecstasy of being, my identity will experience an infinite regress, and I loose myself in the abyss of a nothing that, not being the “nothing” of the Love that wants me ecstatically, is a nothing that is not real, it is nothing-nothing ... And community with others will be a collision and a negation and a distancing to infinity. The peace that is Love is replaced by the war that is hatred.”Note that ecstasy in the above is best read in the Ancient Greek philosophical sense of ἔκστασις (ekstasis), “to be or stand outside oneself, a removal to elsewhere,” since it refers to the self-giving, self-othering nature of love. Removing oneself from the ecstasy of love means retreating into oneself, while God’s love for me being ecstatic underlines His going out of Himself for my sake.

Peppuccio then proceeds to sketch out the Christian approach to relating to others, as a departure from the self-constrained, static nothingness resulting from a withdrawal from ecstatic relationships:

“The Christian revelation has ripped through this way of thinking and of being socially structured from the inside. But we are still far, it seems to me, from having understood this clearly and from having draw practical conclusions from it. It is true, in modern thought duality has been made more dynamic with dialectic. But the logic of confrontation and struggle has not been overcome. Because the relationship between the two “opposing” extremes (I and the other, I and God) is still thought of as ending in one of the two (and, therefore, in the strongest!); while, if Christian faith is true, the relationship does not end in either of the mediated extremes, but in a third that saves them precisely in their diversity. The relationship between two, if it wants to be thought and lived in the logic of God, must be torn from pure (and abstract) symmetry and discovered, as it were, in the asymmetry of a third that “transforms” the opposition into agreement, the conflict into peace.”What is apparent from the above is God’s intrinsic role also in human relationships as the asymmetry that allows for unity in diversity, which very much also prefigures Pope Francis’ insistence in Evangelii Gaudium (§236) that the Church, and society too, ought to be modeled on the polyhedron (where diverse parts preserve their distinctiveness while converging to form one whole) rather than the sphere (where there is total uniformity).

Peppuccio finally leads the above considerations towards reciprocity and freedom in a masterful synthesis:

“In the relationship with God, this means living the relationship with Him, diversity, within Him, in Tri-unity.Reciprocal ecstasy, a mutual being outside oneself, for the other, as a gift for each other, bring identity and dialogue together in love, and, if I too may say so with Peppuccio, are the secret of being.

In the relationship with others, it means “allowing” for God to be among the many, as the “third asymmetrical,” so to speak. This Presence among the many makes diversity true, uniting it without annulling it. This applies to my relationship with myself. It applies to my relationship with the other and with others. Diversity is experienced as love, identity is experienced as love: diversity is experienced as identity, and vice versa. I am me in the infinite, and absolute, gift of myself: in the diversity of me with myself, experienced not as laceration but as ecstatic love. The other, whoever they are, is my giving myself made person, real because giving myself is real. And reciprocally. Without reciprocity what I say here is suffered as an impossibility that must become, but still is not, possible. History, after all, is the path towards a realization of the necessity of this reciprocity so that everyone may be themselves!

From this dialectical perspective “as three,” identity and dialogue are the same thing: they are the love by which I am myself insofar as I am not myself. They are the sign of that freedom-love which is, if I may say so, the secret of being.”

Thank you, Peppuccio, for your wisdom and love!

No comments:

Post a Comment