[Warning: long read :)]

Jesus was a pacifist. To deny this in the face of his own words - “But I say to you, whoever is angry with his brother will be liable to judgment.” (Matthew 5:22), “But I say to you, love your enemies, and pray for those who persecute you.” (Matthew 5:44), “But I say to you, offer no resistance to one who is evil. When someone strikes you on (your) right cheek, turn the other one to him as well.” (Matthew 5:39) and “Put your sword back into its sheath, for all who take the sword will perish by the sword.” (Matthew 26:52) - would be sheer dishonesty.

How about the Church though, has it stuck to Jesus’ pacifist position? Let’s see what it says in the Catechism:

“(§2304) Respect for and development of human life require peace. Peace is not merely the absence of war, and it is not limited to maintaining a balance of powers between adversaries. Peace cannot be attained on earth without safeguarding the goods of persons, free communication among men, respect for the dignity of persons and peoples, and the assiduous practice of fraternity.While the above does talk about circumstances under which war is justified, it is a last resort, acceptable under the simultaneous satisfaction of specific conditions listed above, and has self-defense as its purpose, with indiscriminate destruction and the devastating effects of modern means of warfare ringing alarm bells. During the progress of such self-defense (the only possible trigger for just military action), the Catechism further emphasizes that “The Church and human reason both assert the permanent validity of the moral law during armed conflict. “The mere fact that war has regrettably broken out does not mean that everything becomes licit between the warring parties.” (Gaudium et Spes, 79 § 4)” and proceeds to warn against the abuses so endemic in war and against the accumulation of arms. Finally, the Catechism draws attention to the root causes, of which war can be a symptom, and calls for their treatment:

(§2307) The fifth commandment forbids the intentional destruction of human life. Because of the evils and injustices that accompany all war, the Church insistently urges everyone to prayer and to action so that the divine Goodness may free us from the ancient bondage of war.

(§2308) All citizens and all governments are obliged to work for the avoidance of war. However, “as long as the danger of war persists and there is no international authority with the necessary competence and power, governments cannot be denied the right of lawful self-defense, once all peace efforts have failed.” (Gaudium et Spes, 79 § 4)

(§2309) The strict conditions for legitimate defense by military force require rigorous consideration. The gravity of such a decision makes it subject to rigorous conditions of moral legitimacy. At one and the same time:The power of modern means of destruction weighs very heavily in evaluating this condition. These are the traditional elements enumerated in what is called the “just war” doctrine. The evaluation of these conditions for moral legitimacy belongs to the prudential judgment of those who have responsibility for the common good.

- the damage inflicted by the aggressor on the nation or community of nations must be lasting, grave, and certain;

- all other means of putting an end to it must have been shown to be impractical or ineffective;

- there must be serious prospects of success;

- the use of arms must not produce evils and disorders graver than the evil to be eliminated.

(§2314) “Every act of war directed to the indiscriminate destruction of whole cities or vast areas with their inhabitants is a crime against God and man, which merits firm and unequivocal condemnation.” (Gaudium et Spes, 80 § 3)”

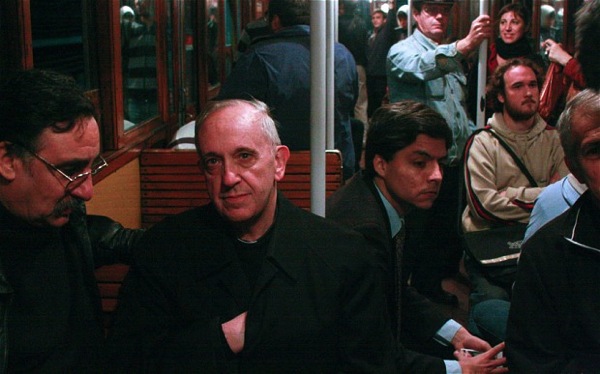

“(§2317) Injustice, excessive economic or social inequalities, envy, distrust, and pride raging among men and nations constantly threaten peace and cause wars. Everything done to overcome these disorders contributes to building up peace and avoiding war.”And Pope Francis, where does he stand? There can be no doubt here that he, like Jesus, is an absolute pacifist:

“War is madness. It is the suicide of humanity. It is an act of faith in money, which for the powerful of the earth is more important than the human being. For behind a war there are always sins. [… War] is the suicide of humanity, because it kills the heart, it kills precisely that which is the message of the Lord: it kills love! Because war comes from hatred, from envy, from desire for power, and – we’ve seen it many times - it comes from that hunger for more power.” (Homily at Domus Sanctae Marthae, 2 June 2013).And Francis is not alone is his radical stance against war, Blessed Pope John Paul II said that “War should belong to the tragic past, to history: it should find no place on humanity’s agenda for the future” and that “Humanity should question itself, once more, about the absurd and always unfair phenomenon of war, on whose stage of death and pain only remain standing the negotiating table that could and should have prevented it.” Benedict XVI too was clear about war being a failure: “War, with its aftermath of bereavement and destruction, has always been deemed a disaster in opposition to the plan of God, who created all things for existence and particularly wants to make the human race one family.”

“We have perfected our weapons, our conscience has fallen asleep, and we have sharpened our ideas to justify ourselves. As if it were normal, we continue to sow destruction, pain, death! Violence and war lead only to death, they speak of death! Violence and war are the language of death! […]

My Christian faith urges me to look to the Cross. How I wish that all men and women of good will would look to the Cross if only for a moment! There, we can see God’s reply: violence is not answered with violence, death is not answered with the language of death. In the silence of the Cross, the uproar of weapons ceases and the language of reconciliation, forgiveness, dialogue, and peace is spoken. […]

violence and war are never the way to peace! Let everyone be moved to look into the depths of his or her conscience and listen to that word which says: Leave behind the self-interest that hardens your heart, overcome the indifference that makes your heart insensitive towards others, conquer your deadly reasoning, and open yourself to dialogue and reconciliation. Look upon your brother’s sorrow and do not add to it, stay your hand, rebuild the harmony that has been shattered; and all this achieved not by conflict but by encounter! […]

Let the words of Pope Paul VI resound again: “No more one against the other, no more, never! ... war never again, never again war!” (Address to the United Nations, 1965).” (Prayer Vigil for Peace, 7 September 2013)

So, you may ask, what is the point of writing about the attitude of Jesus, the Church and recent popes with regard to war, when it is so obviously pacifist and admitting of military self-defense only under almost theoretical, extreme conditions and applying to specific parts of an armed conflict? Sadly there are other, vocal proponents of a very different take on this topic, who - to my mind unbelievably - present their positions as Catholic and who tend to trace them to statements like the following one by George Weigel, who feels supported by Sts. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas:

“Thus those scholars, activists, and religious leaders who claim that the just war tradition “begins” with a “presumption against war” or a “presumption against violence” are quite simply mistaken. It does not begin there, and it never did begin there. To suggest otherwise is not merely a matter of misreading intellectual history (although it is surely that). To suggest that the just war tradition begins with a “presumption against violence” inverts the structure of moral analysis in ways that inevitably lead to dubious moral judgments and distorted perceptions of political reality.”With Jesus and the Church’s position having been stated with such force and clarity over the last decades, I won’t even go to the trouble of addressing positions like Weigel’s point-by-point and would just like to note that they are akin to reading St. Paul and arguing in favor of slavery today. Positions that may be textually consistent with the source they claim justifies them, but that both miss the original author’s intentions (just think about what slavery would be like if “master” and “slave” followed St. Paul’s advice1) and the fact that the Church is the living Mystical Body of Jesus that has considerably matured over the last 2000 years.

1 “Slaves, be obedient to your human masters with fear and trembling, in sincerity of heart, as to Christ, not only when being watched, as currying favor, but as slaves of Christ, doing the will of God from the heart, willingly serving the Lord and not human beings, knowing that each will be requited from the Lord for whatever good he does, whether he is slave or free. Masters, act in the same way toward them, and stop bullying, knowing that both they and you have a Master in heaven and that with him there is no partiality.” (Ephesians 6:5-9) A classic “infiltrate and destroy from within” tactic if ever I saw one.