The other day I came across a beautiful letter written by the poet Ted Hughes to his then 24-year-old son Nicholas, and reading it I was immediately struck by his fatherly love, by the strange familiarity, yet distinctness, of his advice and by the streak of sadness running through it.

The gist of Hughes’ advice derives from the idea that “every single [person] is, and is painfully every moment aware of it, still a child.”:

“It’s something people don’t discuss, because [they] are aware of [it] only as a general crisis of sense of inadequacy, […] or a sense of not having a strong enough ego to meet and master inner storms that come from an unexpected angle. But not many people realise that it is, in fact, the suffering of the child inside them.When I first read this, I immediately had the sense that it contains those “reflected rays of truth” (Nostra Aetate 2); I could sense the traces of Jesus’s words in it - both in the image of the child as the underlying paradigm (“I say to you, unless you turn and become like children, you will not enter the kingdom of heaven.” Matthew 18:3) and in the mechanism of getting to a true “meeting” by having inner child engage with inner child. In fact, if you read on in Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus says: “whoever receives one child such as this in my name receives me” (18:5) and St. Paul elsewhere adds: “yet I live, no longer I, but Christ lives in me” (Galatians 2:20) which takes us to the long-established Christian image of each one of us being Jesus - having Jesus inside. With this key, I can read Hughes’ “child inside” as Jesus, which makes his proposal for how to truly meet another person essentially take us to Jesus’: “where two or three are gathered together in my name, there am I in the midst of them” (Matthew 18:20). If Jesus in me and Jesus in another connect, He is not only in each one of us, but also among us. Our meeting becomes like that of the persons of the Trinity, where the “meeting” itself takes on a level of reality like that of those who meet (“[Y]ou see the Trinity if you see love … They are three: the lover, the loved, and the love.” St. Augustine).

Everybody tries to protect this vulnerable […] eight year old inside, and to acquire skills and aptitudes for dealing with the situations that threaten to overwhelm it. So everybody develops a whole armour of secondary self, the artificially constructed being that deals with the outer world, and the crush of circumstances.

And when we meet people, this is what we usually meet [and we] end up making ‘no contact.’ But when you develop a strong divining sense for the child behind that armour, and you make your dealings and negotiations only with that child, you find that everybody becomes, in a way, like your own child. It’s an intangible thing. But they too sense when that is what you are appealing to, and they respond with an impulse of real life, you get a little flash of the essential person, which is the child.”

Am I saying that this is what Hughes meant? Certainly not. While being clearly distinct, the negative image of a person’s inner child being hidden behind the “armour of [the artificially constructed,] secondary self” does have close parallels with and traces of the Gospel. The difference between Hughes’ “inner child” and Jesus seems to grow further still in the following lines though:

“Usually, that child is a wretchedly isolated undeveloped little being. It’s been protected by the efficient armour, it’s never participated in life, it’s never been exposed to living and to managing the person’s affairs, it’s never been given responsibility for taking the brunt. And it’s never properly lived. That’s how it is in almost everybody. And that little creature is sitting there, behind the armour, peering through the slits. […] At every moment, behind the most efficient seeming adult exterior, the whole world of the person’s childhood is being carefully held like a glass of water bulging above the brim. And in fact, that child is the only real thing in them. It’s their humanity, their real individuality, the one that can’t understand why it was born and that knows it will have to die, in no matter how crowded a place, quite on its own. That’s the carrier of all the living qualities. It’s the centre of all the possible magic and revelation.”This does sound quite unlike Jesus - or does it? Looking more closely, it seems to me that a lot of what Hughes says here is reminiscent of Jesus suffering on the cross, even to the point of feeling abandoned by his Father (“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Mark 15:34). The wretched isolation facing death - that is Jesus on the cross and that is Jesus in me, when I am made to suffer by others or when I make him suffer in me by placing my own interests before those of others. Read in this way, Hughes view of the person and inter-personal relationships, appear in a very Christian light. Here Jesus suffers in those who smother him with an “artificially constructed, secondary self” and shows an “impulse of real life” when he is allowed to meet himself in another person.

Hughes then continues with a seeming contradiction, which, however, supports the above, Christocentric reading:

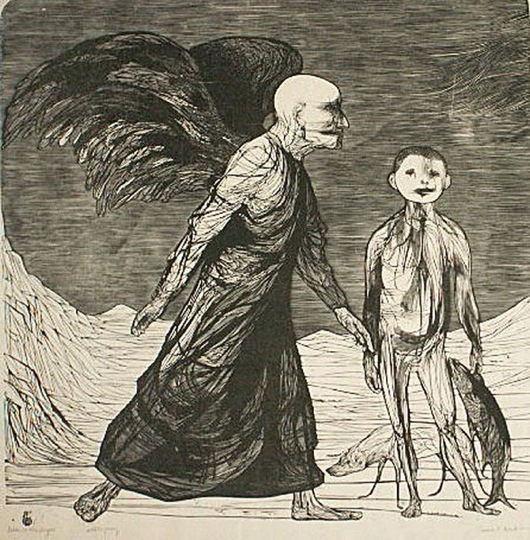

“That’s the paradox: the only time most people feel alive is when they’re suffering, when something overwhelms their ordinary, careful armour, and the naked child is flung out onto the world. […] But when that child gets buried away under their adaptive and protective shells—he becomes one of the walking dead, a monster.”It is in his suffering that Jesus most vividly show’s his love for us, his friends, and it is in suffering that I too am most undeniably called to make a choice between what matters and that “artificial armour” that I allow to obstruct Jesus’ life in me. This is not some morbid fascination with suffering or a form of masochism - on the contrary, it is a realization that in suffering I have an opportunity to encounter Jesus, who then takes me with him to the joy of resurrection. Hughes does not wallow in the negative either and leads his son to the following conclusion:

“[The] only thing people regret is that they didn’t live boldly enough, that they didn’t invest enough heart, didn’t love enough. Nothing else really counts at all. It was a saying about noble figures in old Irish poems—he would give his hawk to any man that asked for it, yet he loved his hawk better than men nowadays love their bride of tomorrow. He would mourn a dog with more grief than men nowadays mourn their fathers.”The call to love that Hughes arrives at is nothing other than Jesus’ challenge to all who came to seek his advice: “love one another as I love you[, for n]o one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends” (John 15:12-13).

If, like me until very recently, you haven’t read any of Hughes’ poetry, here is a great selection - mostly from Crow

No comments:

Post a Comment