I first came across the “principle of charity” thanks to one of the lecturers on the MA in Philosophy that I attended (but sadly not completed) at Sheffield. In the first lecture of the Aristotle module, where we were going to cover Book 9 of the Metaphysics

I first came across the “principle of charity” thanks to one of the lecturers on the MA in Philosophy that I attended (but sadly not completed) at Sheffield. In the first lecture of the Aristotle module, where we were going to cover Book 9 of the MetaphysicsAristotle wrote the Metaphysics in the 4th century BC, using the language of the day and firmly set in the cultural, scientific and political context of the time. If we approach this text without an attempt at looking for something positive, valuable or meaningful, we will very quickly come to dismiss it, as it is very easy to find it dated, set it superseded modes of thinking or irrelevant. This would be a great shame though, as it would keep Aristotle's insights hidden from us. Instead, let's adopt the principle of charity and look for the most favorable interpretation of Aristotle's words - the interpretation that would give his statements the greatest value, the most sense.As you can imagine, I was super enthusiastic about this attitude, since it struck me both as very sensible and like exactly the kind of angle that the Gospels would take, had they addressed the topic of hermeneutics. While looking into the background of this principle, I came across the following example of its application in the context of religion that I found particularly positive:

“The next [human representation of the ideal of divine love] is what is known as Vatsalya, loving God not as our Father but as our Child. This may look peculiar, but it is a discipline to enable us to detach all ideas of power from the concept of God. … [T]he Christian and the Hindu can realize [this idea of God as Child] easily, because they have the baby Jesus and the baby Krishna.”Not only does Vivekanda shed light on an aspect of Christian revelation from a new angle, but he uses it to draw parallels with Hinduism, thereby making both religions' insights accessible to each other's followers. In this context it is particularly rewarding to see how this same point is emphasized in a recent homily of Pope Benedict XVI:

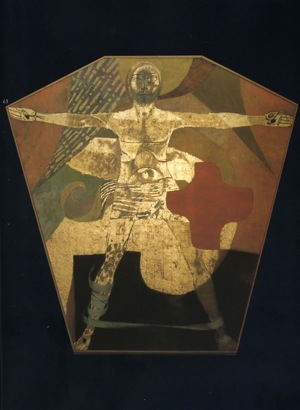

Swami Vivekanda (1863–1902)

“God’s sign is simplicity. God’s sign is the baby. God’s sign is that he makes himself small for us. This is how he reigns. He does not come with power and outward splendor. He comes as a baby – defenseless and in need of our help. He does not want to overwhelm us with his strength. He takes away our fear of his greatness.”Just to avoid the ever-lurking accusation of syncretism when considering inter-religious questions, I don't read Vivekanda as equating Jesus with Krishna or proposing their co–existence or merging, but instead as pointing to principles expressed with similarity in both traditions.

If only the principle of charity were more broadly applied both in secular and religious discourse …

I can't mention Dr. Makin without sharing the following anecdote: One morning Dr. Makin arrives late to give his lecture and with indignation exclaims: “I have been asked to do some administrative work! Can you imagine a professional administrator being asked to write a book about Aristotle?!” I often feel the same (but still have to do it :).